Castell Coch

| Castell Coch | |

|---|---|

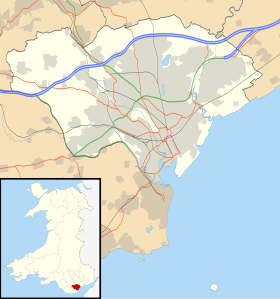

| Tongwynlais, Cardiff, Wales | |

The main entrance to Castell Coch | |

Location shown within Cardiff | |

| Coordinates | 51°32′09″N 3°15′17″W / 51.5358°N 3.2548°W |

| Type | Gothic revival |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Cadw |

| Condition | Intact |

| Website | Castell Coch |

| Site history | |

| Built | Original castle 11th–13th centuries Rebuilt 1875–91 |

| Built by | John Crichton-Stuart William Burges |

| In use | Open to public |

| Materials | Red sandstone rubble, grey limestone and Pennant sandstone |

| Events | Native Welsh rebellion of 1314 |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

Castell Coch (Welsh for 'red castle'; Welsh pronunciation: [ˈkas.tɛɬ koːχ]) is a 19th-century Gothic Revival castle built above the village of Tongwynlais, Cardiff in Wales. The first castle on the site was built by the Normans after 1081 to protect the newly conquered town of Cardiff and control the route along the Taff Gorge. Abandoned shortly afterwards, the castle's earth motte was reused by Gilbert de Clare as the basis for a new stone fortification, which he built between 1267 and 1277 to control his freshly annexed Welsh lands. This castle may have been destroyed in the native Welsh rebellion of 1314. In 1760, the castle ruins were acquired by John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, as part of a marriage settlement that brought the family vast estates in South Wales.

John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute, inherited the castle in 1848. One of Britain's wealthiest men, with interests in architecture and antiquarian studies, he employed the architect William Burges to rebuild the castle, "as a country residence for occasional occupation in the summer", using the medieval remains as a basis for the design. Burges rebuilt the outside of the castle between 1875 and 1879, before turning to the interior; he died in 1881 and the work was finished by Burges's remaining team in 1891. Bute reintroduced commercial viticulture into Britain, planting a vineyard just below the castle, and wine production continued until the First World War. He made little use of his new retreat, and in 1950 his grandson, the 5th Marquess of Bute, placed it into the care of the state. It is now controlled by the Welsh heritage agency Cadw.

Castell Coch's external features and the High Victorian interiors led the historian David McLees to describe it as "one of the greatest Victorian triumphs of architectural composition."[1] The exterior, based on 19th-century studies by the antiquarian George Clark, is relatively authentic in style, although its three stone towers were adapted by Burges to present a dramatic silhouette, closer in design to mainland European castles such as Chillon than native British fortifications. The interiors were elaborately decorated, with specially designed furniture and fittings; the designs include extensive use of symbolism drawing on classical and legendary themes. Joseph Mordaunt Crook wrote that the castle represented "the learned dream world of a great patron and his favourite architect, recreating from a heap of rubble a fairy-tale castle which seems almost to have materialised from the margins of a medieval manuscript."[2]

The surrounding Castell Coch beech woods contain rare plant species and unusual geological features and are protected as a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

History

[edit]11th–14th centuries

[edit]

The first castle on the Castell Coch site was probably built after 1081, during the Norman invasion of Wales.[3][4] It formed one of a string of eight fortifications intended to defend the newly conquered town of Cardiff and control the route along the Taff Gorge.[4] It took the form of a raised, earth-work motte, about 35 metres (115 ft) across at the base and 25 metres (82 ft) on the top, protected by the surrounding steep slopes.[5] The 16th-century historian Rice Merrick claimed that the castle was built by the Welsh lord Ifor ap Meurig, but there are no records of this phase of the castle's history and modern historians doubt this account.[6][7] The first castle was probably abandoned after 1093 when the Norman lordship of Glamorgan was created, changing the line of the frontier.[4]

In 1267, Gilbert de Clare, who held the Lordship of Glamorgan, seized the lands around the town of Senghenydd in the north of Glamorgan from their native Welsh ruler.[4][3][8] Caerphilly Castle was built to control the new territory and Castell Coch — strategically located between Cardiff and Caerphilly—was reoccupied.[4][8] A new castle was built in stone around the motte, comprising a shell-wall, a projecting circular tower, a gatehouse and a square hall above an undercroft.[3][9] The north-west section of the walls was protected by a talus and the sides of the motte were scarped to increase their angle, all producing a small but powerful fortification.[4] Further work followed between 1268 and 1277, which added two large towers, a turning-bridge for the gatehouse and further protection to the north-west walls.[10][a]

On Gilbert's death, the castle passed to his widow Joan and around this time it was referred to as Castrum Rubeum, Latin for "the red castle", probably after the colour of the red sandstone defences.[12][13] Gilbert's son, also named Gilbert, inherited the property in 1307.[14] He died at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, triggering an uprising of the native Welsh in the region.[14] Castell Coch was probably destroyed by the rebels in July 1314, and possibly slighted to put it beyond any further use; it was not rebuilt and the site was abandoned.[14][15]

15th–19th centuries

[edit]Bute ownership

[edit]

Castell Coch remained derelict; the antiquarian John Leland, visiting around 1536, described it as "all in ruin, no big thing but high".[14] The artist and illustrator Julius Caesar Ibbetson painted the castle in 1792, depicting substantial remains and a prominent tower, with a lime kiln in operation alongside the fortification.[16][17] Stone from the castle may have been robbed and used to feed the kilns during this period.[18] A similar view was sketched by an unknown artist in the early 19th century, showing more trees around the ruins; a few years later, Robert Drane recommended the site as a place for picnics and noted its abundance of wild garlic.[17][19][20]

The ruins were acquired by the Earls of Bute in 1760, when John Stuart, the 3rd Earl and, from 1794, the 1st Marquess, married Lady Charlotte Windsor, adding her estates in South Wales to his inheritance.[21] John's grandson, John Crichton-Stuart, developed the Cardiff Docks in the first half of the 19th century; although the docks were not especially profitable, they opened opportunities for the expansion of the coal industry in the South Wales valleys, making the Bute family extremely wealthy.[21][22] The 2nd Marquess carried out exploration for iron ore at Castell Coch in 1827 and considered establishing an ironworks there.[23]

The 3rd Marquess of Bute, another John Crichton-Stuart, inherited the castle and the family estates as a child in 1848.[24][25] On his coming of age, Bute's landed estates and industrial inheritance made him one of the wealthiest men in the world.[26] He had a wide range of interests including archaeology, theology, linguistics and history.[26] Interest in medieval architecture increased in Britain during the 19th century, and in 1850 the antiquarian George Thomas Clark surveyed Castell Coch and published his findings, the first major scholarly work about the castle.[17] The ruins were covered in rubble, ivy, brushwood and weeds; the keep had been largely destroyed and the gatehouse was so covered with debris that Clark failed to discover it.[17][27] Nonetheless, Clark considered the external walls "tolerably perfect" and advised that the castle be conserved, complete with the ivy-covered stonework.[28]

In 1871, Bute asked his chief Cardiff engineer, John McConnochie, to excavate and clear the castle ruins.[29][b] The report on the investigations was produced by William Burges, an architect with an interest in medieval architecture[29] who had met Bute in 1865. The Marquess subsequently employed him to redevelop Cardiff Castle in the late 1860s, and the two men became close collaborators.[30][31] Burges's lavishly illustrated report, which drew extensively on Clark's earlier work, laid out two options: either conserve the ruins or rebuild the castle to create a house for occasional occupation in the summer.[32][33][34][35] On receipt of the report, Bute commissioned Burges to rebuild Castle Coch in a Gothic Revival style.[32][33]

Reconstruction

[edit]

The reconstruction of Castell Coch was delayed until 1875, because of the demands of work at Cardiff Castle and an unfounded concern by the Marquess's trustees that he was facing bankruptcy.[36] On commencement, the Kitchen Tower, Hall Block and shell wall were rebuilt first, followed by the Well Tower and the Gatehouse, and the Keep Tower last.[37][33] Burges's drawings for the proposed rebuilding survive at the Bute seat of Mount Stuart.[34] The drawings were supplemented by a large number of wooden and plaster models, from smaller pieces to full-size models of furniture.[38][c]

The bulk of the external work was complete by the end of 1879. The result closely followed Burges's original plans, with the exception of an additional watch tower intended to resemble a minaret, and some defensive timber hoardings, both of which were not undertaken.[33][37][40] Clark continued to advise Burges on historical aspects of the reconstruction and the architect tested the details of proposed features, such as the drawbridge and portcullis, against surviving designs at other British castles.[41][42]

This concludes the survey of the ruins and my conjectural restoration. As for the latter I must claim your indulgence; for the knowledge of the military architecture of the Middle Ages is a long way from being as advanced as the knowledge of either domestic or ecclesiastical architecture. It is true that Viollet le Duc and Mr. G.T. Clark have taught us a great deal, but we are still very far behind hand and the restoration I have attempted will I hope be judged according to the measure of what is known or ought to be known.

Burges's team of craftsmen at Castell Coch included many who had worked with him at Cardiff Castle and elsewhere.[44] John Chapple, his office manager, designed most of the furnishings and furniture,[44] and William Frame acted as clerk of works.[44] Horatio Lonsdale was Burges's chief artist, painting extensive murals at the castle.[44] His main sculptor was Thomas Nicholls, together with another long-time collaborator, the Italian sculptor Ceccardo Fucigna.[44]

Stimulated by antiquarian writings about British viticulture, Bute decided to reintroduce commercial grape vines into Britain in 1873.[45] He sent his gardener Andrew Pettigrew to France for training and planted a 1.2-hectare (3-acre) vineyard just beneath the castle in 1875.[45][46] The first harvests were poor and the initial harvest in 1877 produced only 240 bottles.[47][48] Punch magazine claimed that any wine produced would be so unpleasant that "it would take four men to drink it — two to hold the victim and one to pour the wine down his throat".[46][48][49] By 1887, the output was 3,000 bottles of sweet white wine of reasonable quality.[49][50][51] Bute persevered, commercial success followed and 40 hogsheads of wine, including a red varietal using Gamay grapes, were produced annually by 1894 to positive reviews.[49][50][51][52]

Burges died in 1881 after catching a severe chill during a site visit to the castle.[53][d] His brother-in-law, the architect Richard Pullan, took over the commission and delegated most of the work to Frame, who directed the work on the interior until its completion in 1891.[1][53] Bute and his wife Gwendolen were consulted over the details of the interior decoration; replica family portraits based on those at Cardiff were commissioned to hang on the walls.[55][56] Clark approved of the result, commenting in 1884 that the restoration was in "excellent taste".[57] An oratory originally built on the roof of the Well Tower was removed before 1891 but in other respects the completed castle was left unaltered.[58]

The castle was not greatly used; the Marquess rarely visited after its completion.[1] The property had probably only been intended for limited, informal use, for example as a retreat following picnics. Although it had reception rooms suitable for large gatherings, it had only three bedrooms and was too far from Cardiff for casual visits.[59][36][e] The restored castle initially received little interest from the architectural community, possibly because the total rebuilding of the castle ran counter to the increasingly popular late-Victorian philosophy of conserving older buildings and monuments.[61]

20th–21st centuries

[edit]

Bute died in 1900 and his widow, the Marchioness, was given a life interest in Castell Coch; during her mourning, she and her daughter, Lady Margaret Crichton-Stuart, occupied the castle and made occasional visits thereafter.[1][62] Production in the castle vineyards ceased during the First World War due to the shortages of the sugar needed for the fermentation process, and in 1920 the vineyards were uprooted.[49] John, the 4th Marquess, acquired the castle in 1932 but made little use of it.[59] He also began to reduce the family's investments in South Wales.[63] The coal trade had declined after 1918 and industry had suffered during the depression of the 1920s;[64][65] by 1938, the great majority of the family interests, including the coal mines and docks, had been sold off or nationalised.[63]

The 5th Marquess of Bute, another John, succeeded in 1947 and, in 1950, he placed the castle in the care of the Ministry of Works. The donation was accepted only with reluctance; in the post-war period Burges's reputation, and that of Victorian architecture more generally, were at their lowest ebb, and the castle was considered a "hideous Victorian joke".[66][f] The Marquess also disposed of Cardiff Castle, which he gave to the city, removing the family portraits from the castle before doing so. In turn, the paintings in Castell Coch were removed by the ministry and sent to Cardiff,[56] the National Museum of Wales providing alternatives from their collection for Castell Coch.[56] Many of the original furnishings, removed in 1950, have been recovered in the later 20th and 21st centuries and returned to their original locations in the castle.[1] Two stained-glass panels from the demolished chapel, lost since 1901, were rediscovered at an auction in 2010 and were bought by Cadw for £125,000 in 2011.[68] Academic interest in the property grew, with publications in the 1950s and 1960s exploring its artistic and architectural value.[69] Since 1984, the property has been administered by Cadw, an agency of the Welsh Government, and is open to the public; it typically receives between 50,000 and 75,000 visits per year; this number dropped during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 23,095 people visited in 2021.[70][g] The Drawing Room is available for wedding ceremonies.[74]

The castle has been used as a location for films and television programmes, including The Black Knight (1954), Sword of the Valiant (1984), The Worst Witch (1998), Wolf Hall (2015) and several episodes of Doctor Who.[75][76][77][78]

The castle's exposed position causes it to suffer from penetrating damp and periodic restoration has been necessary.[55][79] The stone tiles on the roof were replaced by slate in 1972, a programme of repair was carried out on the Keep in 2007 and interior conservation work was undertaken in 2011 to address problems in Lady Bute's Bedroom, where damp had begun to damage the finishings.[55][79][80][81] In 2017 a systematic restoration of the three towers was begun, to secure the exteriors and protect the interiors which had continued to deteriorate due to water ingress. Work on the Keep tower was completed in 2019, a two-year programme to repair the Well tower began in 2024, and Cadw has started planning for a similar restoration of the Kitchen tower.[82] The castle will remain open to visitors throughout the restoration work.[83]

Architecture

[edit]Overview

[edit]Castell Coch occupies a stretch of woodland on the slopes above the village of Tongwynlais and the River Taff, about 10.6 kilometres (6.6 mi) north-west of the centre of Cardiff.[84][85] The architecture is High Victorian Gothic Revival in style, influenced by contemporary 19th-century French restorations.[86] Its design combines the surviving elements of the medieval castle with 19th-century additions to produce a building which the historian Charles Kightly considered "the crowning glory of the Gothic Revival" in Britain.[87] John V. Hiling, in his study The Architecture of Wales: From the first to the twenty-first century, suggests that Castell Coch, and Cardiff Castle, are "the most remarkable domestic buildings to be resurrected in the nineteenth century."[88][h] The castle is protected under UK law as a Grade I listed building due to its exceptional architectural and historical interest.[30][81][86]

Exterior

[edit]

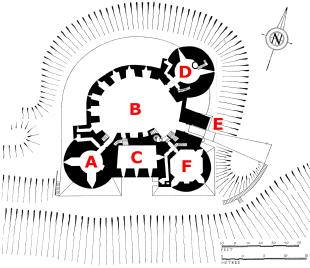

- A – Kitchen Tower

- B – Courtyard

- C – Hall Block

- D – Well Tower

- E – Gatehouse

- F – Keep

The castle comprises three circular towers—the Keep, the Kitchen Tower and the Well Tower—along with the Hall Block, the Gatehouse and a shell wall; the buildings almost entirely encase the original motte in stone.[89] The older parts of the castle are constructed from crudely laid red sandstone rubble and grey limestone, the 19th-century additions in more precisely cut red Pennant sandstone.[33][90] A ditch is cut out of the rock in front of the Gatehouse and leads to an eastern approach road.[91] The castle is surrounded by woodland and the 19th-century vineyards below it have been converted into a golf course.[92] In 1850, George Clark recorded an "outer court" of which nothing remains; this may, in fact, have been the traces of the earlier lime kiln operations around the site.[93]

The Gatehouse is reached across a wooden bridge, incorporating a drawbridge.[94] Burges intended the bridge to copy those of medieval castles, which he believed were designed to be easily set on fire in the event of attack.[94] The Gatehouse was fitted with a wooden defensive bretèche[i] and, above the entrance, Burges sited a portcullis and a glazed statue of the Madonna and Child sculpted by Ceccardo Fucigna.[44][94]

The Keep is 12 metres (39 ft) in diameter with a square, spurred base; in the 13th century there would have been an adjacent turret, on the south-west side, containing latrines, but few traces remain.[95] There is no evidence that the tower that Burges termed a keep would have fulfilled this function in the medieval period and he appears to have chosen the name because of his initial decision to locate the bedrooms of Lord and Lady Bute in the rebuilt tower.[95] The Kitchen Tower is also 12 metres (39 ft) across and rests on a square, spurred base.[96] It was originally two storeys high and contained the medieval kitchen; Burgess raised its height and gave it a conical roof and chimneys.[96] The walls of these two towers are around 3.0 metres (10 ft) thick at the base, thinning to 0.61 metres (2 ft) at the top.[94] The Well Tower at 11.5 metres (38 ft) in diameter is slightly narrower than the Keep or Kitchen Tower, with a well in its lowest chamber sunk into the ground.[97] The Well Tower lacks the spurs of the other two towers and has a flat rather than curved back, facing onto the courtyard, similar to some of the towers built at Caerphilly by the de Clares.[98]

The towers contribute to what the architectural writer Charles Handley-Read considered the castle's "sculptural and dramatic exterior".[99] Almost equal in diameter, but of differing conical roof designs and heights, and topped with copper-gilt weather vanes, they combine to produce a romantic appearance,[3][91][100] which Matthew Williams described as bringing "a Wagnerian flavor to the Taff Valley".[101]

As nearly every Castle in the country has been ruined for more than two centuries ...it is not surprising that no examples are to be found. But we may form a very fair idea of the case if we consult contemporary [manuscripts] and if we do we find nearly an equal number of towers with flat roofs as those with pointed roofs. The case appears to me to be thus: if a tower presented a good situation for military engines, it had a flat top; if the contrary, it had a high roof to guarantee the defenders from the rain and the lighter sorts of missiles.

The design of the towers was influenced by the work of the contemporary French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, including his restorations of Carcassonne and the châteaus of Aigle and Chillon.[31] While the exterior of Castell Coch is relatively true to English 13th-century medieval design—albeit heavily influenced by the Gothic Revival movement—the inclusion of the conical roofs, which more closely resemble those of fortifications in France or Switzerland than of Britain, is historically inaccurate.[31][87][102][103] Although he mounted a historical defence (see box), Burges chose the roofs mainly for architectural effect, arguing that they appeared "more picturesque", and to provide additional room for accommodation in the castle.[102]

The three towers lead into a small oval courtyard that sits on the top of the motte, about 19.5 metres (64 ft) across lengthways.[96] Cantilevered galleries and wall-walks run around the inside of the courtyard with neat and orderly woodwork; the historian Peter Floud critiqued it as "perhaps too much like the backcloth for an historical pageant".[100][104] Burges reconstructed the shell wall that runs along the north-west side of the courtyard 0.99 metres (3 ft 3 in) thick, complete with arrow holes and a battlement.[59]

Interior

[edit]The Keep, the Well Tower and the Kitchen Tower incorporate a series of apartments, of which the main sequence, the Castellan's Rooms, lies within the Keep. The Hall, the Drawing Room, Lord Bute's Bedroom and Lady Bute's Bedroom form a suite of rooms that exemplify the High Victorian Gothic style of 19th century Britain. Unlike the exterior of the castle, which deliberately imitated the architecture of the 13th century, the interior was purely High Victorian in style.[37] On Burges's decoration of Cardiff Castle and Castell Coch, Handley-Read wrote: "I have yet to see any High Victorian interiors from the hand, very largely, of one designer, to equal either in homogeneity or completeness, in quality of execution or originality of conception the best of the interiors of the Welsh castles. For sheer power of intoxication, Burges stand[s] unrivalled."[105]

The Banqueting Hall

[edit]

The Banqueting Hall is 6.1 by 9.1 metres (20 by 30 ft) across with an 11-metre (35 ft) ceiling, and occupies the whole of the first floor of the Hall Block.[106] Burges persuaded Bute and the antiquarian George Clark that the medieval hall would have stood on the first floor.[41] His original plan saw access via one of two equally circuitous routes through the Well Tower or around the entire internal gallery to enter the hall through a passage next to the Drawing Room.[41] Neither approach was acceptable to Bute and at a late stage, around 1878/9, the present entrance was created by expanding a window at the head of the internal gallery.[41]

The hall is austere; the architectural historian John Newman critiqued its decoration as "dilute" and "unfocused", Crook as "anaemic".[107][108] It features stencilled ceilings and murals which resemble medieval manuscripts. The murals were designed by Horatio Lonsdale and executed by Campbell, Smith & Company.[109][108] The furniture is by John Chapple, made in Lord Bute's workshops at Cardiff.[108] The tapered chimney of the room, modelled on 15th-century French equivalents, contains a statue carved by Thomas Nicholls.[109] Although the architectural historian Mark Girouard suggested that the statue depicts the Hebrew King David, most historians believe that it shows Lucius of Britain, according to legend the founder of the diocese of Llandaff in nearby Cardiff.[100][106][109]

The Drawing Room

[edit]

The octagonal Drawing Room occupies the first and second floors of the Keep.[56] The ceiling is supported by vaulted stone ribs modelled on Viollet-Le-Duc's work at Château de Coucy and the lower and upper halves of the room are divided by a minstrels' gallery.[110][111] The original plans for the space involved two chambers, one on each floor, and the new design was adopted only in 1879, Burges noting at the time that he intended to "indulge in a little more ornament" than elsewhere in the castle.[112][113]

The decoration of the room focuses on what Newman described as the "intertwined themes [of] the fecundity of nature and the fragility of life".[56][114] A fireplace by Thomas Nicholls features the Three Fates, the trio of Greek goddesses who are depicted spinning, measuring and cutting the thread of life.[100][115] The ceiling's vaulting is carved with butterflies, reaching up to a golden sunburst at the apex of the room, while plumed birds fly up into a starry sky in the intervening sections.[110][116] Around the room, 58 panels, each depicting one or more unique plants, are surmounted by a mural showing animals from twenty-four of Aesop's Fables. The plants are wild flowers from the Mediterranean, where Lord Bute spent his winter months each year. Carved birds, lizards and other wildlife decorate the doorways.[116]

The historian Terry Measham wrote that the Drawing Room and Lady Bute's Bedroom, "so powerful in their effect, are the two most important interiors in the castle."[117] The architectural writer Andrew Lilwall-Smith considered the Drawing Room to be "Burges's pièce de résistance", encapsulating his "romantic vision of the Middle Ages".[100] The decoration of the ceiling, which was carried out while Burges was alive, differs in tone from the treatment of the murals, and the decoration of Lady Bute's Bedroom, which were both completed, under the direction of William Frame and Horatio Lonsdale respectively, after Burges's death.[115][118] Burges's work is distinctively High Gothic in style, while the later efforts are more influenced by the softer colours and character of the Aesthetic movement, which had grown in popularity by the 1880s.[53][115]

Lord Bute's Bedroom

[edit]In comparison to other rooms within the castle, Lord Bute's Bedroom, sited above the Winch Room, is relatively small and simple.[119] The original plan had Bute's personal accommodation in the Keep but the expansion of the Drawing Room to a double-height room in 1879 required a late change of plan.[111] The bedroom contains an ornately carved fireplace.[120] Doors lead off the room to an internal balcony overlooking the courtyard and to the bretache over the gate arch.[119] The furniture is mainly by Chapple and post-dates Burges, although the washstand and dressing table are pared-down versions of two pieces – the Narcissus Washstand and the Crocker Dressing Table – that Burges made for his own home in London, The Tower House.[121]

This bedroom is also less richly ornamented than many in the castle, making extensive use of plain, stencilled geometrical patterns on the walls.[122] Crook suggested this provided some "spartan" relief before the culmination of the castle in Lady Bute's Bedroom but Floud considered the result "thin" and drab in comparison with the more richly decorated chambers.[122][123] The bedroom would have been impractical for regular use, lacking wardrobes and other storage.[124]

Lady Bute's Bedroom

[edit]Lady Bute's Bedroom comprises the upper two floors of the Keep, with a coffered, double-dome ceiling that rises up into the tower's conical roof.[125] The room was completed after Burges's death and, although he had created an outline model for the room's structure, which survives, he did not undertake detailed plans for its decoration.[118][123][125] His team attempted to fulfil his vision for the room—"would Mr Burges have done it?" William Frame asked Nicholls in a letter of 1887—but the interior decoration was the work of Lonsdale between 1887 and 1888, with considerable involvement from Bute and his wife.[118][123]

The room is circular, with the window embrasures forming a sequence of arches around the outside.[123] It is richly decorated, with love as the theme, displaying carved monkeys, pomegranates and grapevines on the ceiling, and nesting birds topping the pillars.[123][125] Lord Bute thought the monkeys inappropriately "lascivious".[123] Above the fireplace is a winged statue of Psyche, the Greek goddess of the soul, carrying a heart-shaped shield which displays the arms of the Bute family.[100] The washbasin, designed by John Chapple, has a dragon tap, and cisterns for hot and cold water covered with crenellated towers.[123] The Marchioness's scarlet and gold bed is the most notable piece of furniture in the room, modelled on a medieval original drawn by Viollet-le-Duc.[126][123] Crook described the bed as being "medieval to the point of acute discomfort".[123]

The bedroom is Moorish in style, a popular inspiration in mid-Victorian interior design, and echoes earlier work by Burges in the Arab Room at Cardiff Castle and in the chancel at St Mary's Church at Studley Royal in Yorkshire.[125][126] Lilwall-Smith likened the chamber, with its "Moorish-looking dome, maroon-and-gold painted furniture and large, low bed decorated with glass crystal orbs", to a scene from the Arabian Nights.[100] Peter Floud criticised the eclectic nature of this Moorish theme and contrasted it unfavourably with the more consistent style Burges applied to the Arab Room, suggesting that it gave the bedroom an overly theatrical, even pantomime-like, character.[127] The historian Matthew Williams considered that Lonsdale's efforts lack the imagination and flair that Burges himself might have brought to the room.[53]

Other rooms

[edit]The Windlass Room, or Winch Room, is in the Gatehouse, entered from the Drawing Room.[116] It contains a working mechanism for operating the drawbridge and the portcullis.[128] The equipment was originally intended for the second floor, which Burges considered the most historically authentic location.[129] When later design modifications led him to move Lord Bute's Bedroom into that space, the equipment was simplified and placed on the first floor.[129][j] The Windlass Room includes murder holes, which Burges thought would have enabled medieval inhabitants of the castle to pour boiling water and oil on attackers.[122][128]

An oratory or chapel, originally fitted to the roof of the Well Tower but removed before 1891, was decorated with twenty stained glass windows.[58][131] Ten of these windows are displayed at Cardiff Castle, while the other ten are displayed on site; two missing windows having been returned to the castle in 2011.[132] Pullan, in a paper read to the annual meeting of the Royal Institute of British Architects on 17 April 1882, just before the first anniversary of Burges's death, included a description of the chapel; "of wooden construction, partly projecting on immense wooden brackets towards the courtyard, and forming a most picturesque object".[133] Other rooms in the castle include Lady Margaret Bute's Bedroom, the servants' hall and the kitchen.[134]

Interior design details

[edit]- Interior design details at Castell Coch

-

One of the tiled windows embrasures

-

A woodland scene in Lord Bute's Bedroom

-

Murals in the Drawing Room depicting Aesop's Fables ...

-

the room's vaulted ceiling

-

the Three Fates

-

... and more detailed design.

-

Nesting birds in Lady Bute's Bedroom ...

-

...the coffered ceiling ...

-

... and the crystal detailing of her bed

Landscape – Site of Special Scientific Interest

[edit]

The woods surrounding the castle, known as the Taff Gorge complex, are among the most westerly natural beech woodlands in the British Isles.[135] They contain dog's mercury, ramsons, sanicles, bird's-nest orchid, greater butterfly-orchid and yellow bird's nest plants.[135] The area has unusual rock outcrops, which show the point where Devonian Old Red Sandstone and Carboniferous Limestone beds meet; the Castell Coch Quarry is in the vicinity.[136] The area is protected as the Castell Coch Woodlands and Road Section Site of Special Scientific Interest.[137]

The woods above the castle are accessible to the public and are used for walking, mountain biking and horse riding.[138] To the southeast of the castle, a nine-hole golf course occupies the site of the former vineyard.[139]

See also

[edit]- List of castles in Wales

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- Grade I listed buildings in Cardiff

- Guédelon Castle, a project to build an authentic recreation of a 13th-century castle

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The historian David McLees, writing prior to the publication of the Royal Commission's survey on Castell Coch, suggested that the evidence for the chronology of the medieval castle was "inconclusive", but argued that the shell walls and stone apron might have been built in the mid-12th century, with the first round tower possibly built by the de Clares in the early to mid-13th century.[11] The Royal Commission's survey noted that the comprehensive inventories of the de Clare possessions in 1263, and the lists of payments to their castle garrisons in the same year, make no reference to any castle at the site, and found no evidence for an earlier dating.[4]

- ^ John McConnochie is also called James McConnochie in some sources.

- ^ The model of Lady Bute's Bedroom was photographed for an article by W. Howell in 1951 but then vanished, presumed destroyed. It was rediscovered at the Bute property of Dumfries House, Ayrshire, in 2002. The other models were stored at Cardiff Castle, in the Model Room of the Black Tower but were probably destroyed in the late 1940s.[39]

- ^ For much of the 19th century, "a chill" was used as a diagnosis for illness involving a fever and associated chills, in contrast to modern medical approaches which would regard a fever and chills as symptoms of an underlying disease.[54]

- ^ For comparison, on the other side of the Severn Estuary, Dunster Castle, a motte and shell-keep medieval castle, was being remodelled by the architect Anthony Salvin at around this time, specifically to enable the property to meet late 19th-century standards of facilities and accommodation.[60]

- ^ Burges's work at Cardiff Castle was held in similarly low esteem. James Lees-Milne visited Cardiff in 1944 on behalf of the National Trust and made no attempt to conceal his disdain; "inside and out, the most hideous building I have ever seen".[67]

- ^ Visitor numbers for recent years were 8,610 in 2020,[70] 58,937 in 2019,[71] 50,511 in 2018[72] and 75,710 in 2017.[73]

- ^ Hiling writes of the two castles' "sheer ostentatious extravagance and sumptuous theatricality".[88]

- ^ A bretèche is a defensive structure overhanging a castle wall. Commonly of timber, it allowed defenders to drop damaging objects onto attackers below. A similar bretèche, since removed, was constructed by Burges on the walls at Cardiff Castle.

- ^ The portcullis was the subject of discussion following the reading of a paper on Burges's work delivered to the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1882. Pullan, the paper's author, wrote; "I can imagine the construction of this portcullis - perhaps the only one of modern days - was quite after Burges's own heart, and that he would have spent on its contrivance more time than many of his contemporaries would spend upon a design for a house". In an otherwise complimentary reminisce, fellow architect Ewan Christian was dismissive of the effort expended; "It strikes me that this was a pure waste. What do we want with portcullises in these days? It may be a nice and ingenious study, but [.] we want to adapt ourselves to the requirements of the day, and not to be studying how to construct things that never can again be serviceable".[130]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e McLees 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Crook 2013, p. 270.

- ^ a b c d Newman 1995, p. 315.

- ^ a b c d e f g Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 106.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, pp. 105–106.

- ^ McLees 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, pp. 106, 110.

- ^ a b Davies 2006, p. 282.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, pp. 107–108.

- ^ McLees 2005, p. 8.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 105.

- ^ McLees 2005, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 108.

- ^ McLees 2005, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Rousham 1985, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 110.

- ^ McLees 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Brown 2011, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Floud 1954, p. 4.

- ^ a b McLees 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Davies 1981, p. 272.

- ^ Davies 1981, p. 221.

- ^ Hannah 2012, p. 4.

- ^ McLees 2005, p. 14.

- ^ a b Crook 2013, p. 231.

- ^ Clark 1884, pp. 360–364.

- ^ Clark 1884, pp. 362, 364.

- ^ a b Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 112.

- ^ a b McLees 2005, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Redknap 2002, p. 13.

- ^ a b Redknap 2002, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c d e Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 113.

- ^ a b Brown 2011, p. 74.

- ^ McLees 2005, p. 22.

- ^ a b McLees 2005, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Brown 2011, p. 75.

- ^ Williams 2003, p. 271.

- ^ Williams 2003, pp. 269, 271.

- ^ Floud 1954, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d McLees 2005, p. 38.

- ^ Floud 1954, pp. 7, 9.

- ^ Jones 2005, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f McLees 2005, pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Pettigrew 1926, pp. 26, 28.

- ^ a b Lilwall-Smith 2005, p. 239.

- ^ Carradice 2014.

- ^ a b Pettigrew 1926, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d "Light Shed on Vineyard Steeped in History". WalesOnline. 22 February 2005.

- ^ a b Davies 1981, p. 141.

- ^ a b Bunyard & Thomas 1906, p. 251.

- ^ Saintsbury 2008, p. 293.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2003, p. 272.

- ^ Misselbrook 2001, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Kightly 2005, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d e Floud 1954, p. 13.

- ^ Clark 1884, p. 364.

- ^ a b Brown 2011, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Floud 1954, p. 18.

- ^ Garnett 2003, pp. 32, 35.

- ^ Brown 2011, pp. 68–71, 75–76.

- ^ Williams 2003, p. 276.

- ^ a b Benham 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Jenkins 2002, pp. 26, 33.

- ^ Nicholas 1872, p. 461.

- ^ Williams 2019, p. 199.

- ^ Williams 2019, p. 196.

- ^ Carradice, Phil (1 April 2011). "Burges' Stained Glass Panels Return Home to Castell Coch". BBC Wales. Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Brown 2011, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b Davies & Pillsworth 2022, p. 48.

- ^ Davies 2022, p. 61.

- ^ McAllister 2020, p. 44.

- ^ McAllister 2018, p. 39.

- ^ "Weddings and wedding photography". Cadw. Cadw. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Creighton & Higham 2003, p. 65.

- ^ "Children explore and film crews roam where once wizards walked". Wales Online. 27 March 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ Reeves, Megan (4 March 2016). "14 Doctor Who locations that were recycled for new episodes". Radio Times. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ McCrum, Kirstie (21 January 2015). "Find Wolf Hall in Wales with location guide that includes 4 of our awe-inspiring castles". Wales Online. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ a b Historic Wales and Welsh Assembly Government. "Case Study: Conservation Achievements, Castell Coch" (PDF). Cadw. p. 38. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Castell Coch – Lady Bute's Bedroom". Cadw. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Historic Wales Report". Historic Wales. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Restoring Castell Coch to its fairytale glory - a conservation timeline". Cadw. 2024. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ "Preserving Castell Coch and restoring its timeless splendour". Cadw. 2024. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ Route from Cardiff Castle to Castell Coch on Google Maps, Retrieved 7 April 2015

- ^ Cormack 1982, p. 172.

- ^ a b Cadw. "Castell Coch, Tongwynlais (Grade I) (13644)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ a b Kightly 2005, p. 74.

- ^ a b Hiling 2018, p. 179.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Ashurst & Dimes 2011, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, pp. 106, 113.

- ^ Carradice, Phil (5 September 2014). "The Castell Coch Vineyard". BBC Wales. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d Floud 1954, p. 8.

- ^ a b Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 121.

- ^ a b c Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 116.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, pp. 121–123.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales 2000, p. 122.

- ^ Ferriday 1963, p. 208.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lilwall-Smith 2005, p. 240.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Girouard 1979, p. 340.

- ^ Creighton & Higham 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Floud 1954, p. 9.

- ^ Ferriday 1963, p. 209.

- ^ a b Floud 1954, p. 12.

- ^ Newman 1995, p. 317.

- ^ a b c Crook 2013, p. 266.

- ^ a b c Girouard 1979, p. 341.

- ^ a b Crook 2013, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b McLees 2005, p. 29.

- ^ Crook 2013, p. 267.

- ^ Floud 1954, p. 14.

- ^ Newman 1995, p. 318.

- ^ a b c McLees 2005, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Floud 1954, p. 15.

- ^ Measham 1978, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Williams 2003, pp. 271–272.

- ^ a b McLees 2005, p. 46.

- ^ Quinn 2008, p. 144.

- ^ McLees 2005, p. 47.

- ^ a b c Floud 1954, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Crook 2013, p. 269.

- ^ Williams 2003, p. 275.

- ^ a b c d Floud 1954, p. 17.

- ^ a b McLees 2005, p. 49.

- ^ Floud 1954, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b McLees 2005, p. 45.

- ^ a b Floud 1954, pp. 15–16.

- ^ RIBA 1882, p. 197.

- ^ McLees 2005, p. 52.

- ^ Carradice 2011.

- ^ RIBA 1882, p. 191.

- ^ McLees 2005, pp. 50–53.

- ^ a b "Site of Special Scientific Interest". Countryside Council for Wales. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ Strahan & Cantrill 1902, pp. 27–28.

- ^ "Castell Coch Woodlands and Road Section". Countryside Council for Wales. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "Castell Coch". Woodland Trust. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Castell Coch Golf Club". Welshgolfcourses.com. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Ashurst, John; Dimes, Francis G. (2011). Conservation of Building and Decorative Stone. Vol. 2. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-750-63898-2.

- Benham, Stephen (March 2001). "Glamorgan Estate of Lord Bute collection" (PDF). National Archives. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Brown, Wayde Alan (2011). Making History: The Role of Historic Reconstructions Within Canada's Heritage Conservation Movement (Ph.D.). Cardiff, UK: Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University.

- Bunyard, George; Thomas, Owen (1906). The Fruit Garden (2nd ed.). London, UK: Country Life. OCLC 10478232.

- Clark, George T. (1884). Mediaeval Military Architecture in England. Vol. 1. London, UK: Wyman and Sons. OCLC 832406638.

- Cormack, Patrick (1982). Castles of Britain. New York, US: Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0-517-27544-3.

- Creighton, Oliver; Higham, Robert (2003). Medieval Castles. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Archaeology. ISBN 978-0-747-80546-5. OCLC 51682164.

- Crook, J. Mordaunt (2013). William Burges and the High Victorian Dream. London, UK: Francis Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-711-23349-2.

- Davies, John (1981). Cardiff and the Marquesses of Bute. Cardiff, UK: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-708-32463-9.

- Davies, R. R. (2006). The Age of Conquest: Wales 1063–1415. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-20878-5.

- Davies, Michael; Pillsworth, Angharad (2022). Visits to Tourist Attractions in Wales 2021 (PDF). Cardiff: Welsh Government. ISBN 978-1-803-64678-7.

- Davies, Michael (2022). Visits to Tourist Attractions in Wales 2019 & 2020 (PDF). Cardiff: Welsh Government. ISBN 978-1-803-91427-5.

- Ferriday, Peter (1963). Victorian Architecture. London, UK: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 911370.

- Floud, Peter (1954). Castell Coch, Glamorgan. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 13013090.

- Garnett, Oliver (2003). Dunster Castle, Somerset. London, UK: The National Trust. ISBN 978-1-843-59049-1.

- Girouard, Mark (1979). The Victorian Country House. New Haven, US: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02390-9.

The Victorian Country House.

- Hannah, Rosemary (2012). The Grand Designer: Third Marquess of Bute. Edinburgh, UK: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-780-27027-2.

- Hiling, John B. (2018). The Architecture of Wales: From the First to the Twenty-First Centuries. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-786-83285-6.

- Jenkins, Philip (2002). The Making of a Ruling Class: the Glamorgan Gentry 1640–1790. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52194-9.

- Jones, Nigel R. (2005). Architecture of England, Scotland, and Wales. Westport, US: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31850-4.

- Kightly, Charles (2005). Living Rooms: Interior Decoration in Wales 400–1960. Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-857-60227-2.

- Lilwall-Smith, Andrew (2005). Period Living & Traditional Homes Escapes. Andover, UK: Jarrold Publishing. ISBN 978-0-711-73594-1.

- McAllister, Fiona (2020). Visits to Tourist Attractions in Wales 2018 (PDF). Cardiff: Welsh Government. ISBN 978-1-789-64341-1.

- McAllister, Fiona (2018). Visits to Tourist Attractions in Wales 2017 (PDF). Cardiff: Welsh Government. ISBN 978-1-839-33782-6.

- McLees, David (2005) [1998]. Castell Coch (Revised ed.). Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-857-60210-4.

- Measham, Terry (1978). Castell Coch and William Burges. London, UK: Department of the Environment. ISBN 978-0-860-56004-3.

- Misselbrook, David (2001). Thinking about Patients. Plymouth, UK: Petroc Press. ISBN 978-1-900-60349-2.

- Newman, John (1995). The Buildings of Wales: Glamorgan. London, UK: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-140-71056-4.

- Nicholas, Thomas (1872). Annals and Antiquities of the Counties and County Families of Wales. London, UK: Longmans. OCLC 4948061.

Annals and Antiquities of the Counties and County Families of Wales.

- Quinn, Tom (2008). Hidden Britain. London, UK: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-847-73129-6.

- Pettigrew, A. A. (1926). "Welsh Vineyards". Transactions of the Cardiff Naturalists' Society. 59: 25–34.

- Redknap, Mark (2002). Re-Creations: Visualising Our Past. Cardiff, UK: National Museum of Wales and Cadw. ISBN 978-0-720-00519-6.

- RIBA (1882). Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects 1881-82. London: Royal Institute of British Architects. OCLC 461039989.

- Rousham, Sally (1985). Castell Coch. Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-0-948-32905-0.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (2000). An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Glamorgan. Vol. III, Medieval Secular Monuments, Part 1b, The Later Castles from 1217 to the Present. Aberystwyth, UK: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. ISBN 978-1-871-18422-8.

- Saintsbury, George (2008) [1920]. Pinney, Thomas (ed.). Notes on a Cellar-Book. Berkeley US, and Los Angeles, US: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-94240-0.

- Strahan, Aubrey; Cantrill, Thomas Crosbee (1902). The Geology of the South Wales Coal-field, Part III. London, UK: His Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 9780118844024. OCLC 314554082.

- Williams, Matthew (2003). "Lady Bute's Bedroom, Castell Coch: A Rediscovered Architectural Model". Architectural History. 46: 269–276. doi:10.2307/1568810. JSTOR 1568810.

- — (2004). William Burges. Norwich, UK: Jarrold Publishing. ISBN 978-1-841-65139-2.

- — (2019). Cardiff Castle and the Marquesses of Bute. London: Scala Arts & Heritage Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1-785-51234-6. OCLC 1097577215.